The

Ciudad Estudiantil was located next to the Children’s City in the

Buenos Aires suburb of Belgrano. It took up four city blocks: Echeverría,

Ramsay, Dragones, and Blanco Encalada. The

Ciudad Estudiantil was located next to the Children’s City in the

Buenos Aires suburb of Belgrano. It took up four city blocks: Echeverría,

Ramsay, Dragones, and Blanco Encalada.

It was organized in the same way as the Hogar Escuelas. Students were

transported to their secondary (high) schools each day in Fundacion buses

and received tutoring if needed when they returned to the Student City

at the end of the school day. Classes were also taught at the Student

City and special emphasis was placed on instruction in the latest advances

in technology to ensure they were prepared to be successful in the modern

world. The instruction the students received at the Student City was far

ahead of what most secondary establishments offered; when the military

closed the City after the 1955 coup d’etat, many students were offered

scholarships in other countries eager to take advantage of their skills.

Both the Ciudad Infantil and the Ciudad Estudiantil were ahead of their

time. The purpose of the Ciudad Estudiantil was not only to funcion as

a Hogar Escuela for adolescents in need but also to prepare future leaders

from among the working classes by involving them in the decision-making

process of governing the Ciudad Estudiantil.

All students were male. Since the Fundacion did not yet have a Ciudad

Estudiantil for females, adolescent girls continued to be under the protection

of the Hogares Escuelas; they received food, clothes, medical attention,

tuition to secondary schools, books, supplies, everything they needed

to complete their secondary schooling (the only condition was that they

had to pass all their classes, but tutoring was always available).

The

City contained replicas of the offices in the Casa Rosada (where the President

worked but did not live). Students chose a president, ministers and diplomats

who were encouraged to offer suggestions and constructive criticism. Everyone

had a job to do, from welcoming newcomers and helping them to adapt to

the City or forming part of the nightly security patrol to holding an

elective office. Based on his personality, an adolescent might have his

own room or share a room with one or two other students. Students were

responsible for maintaining order in their own rooms and for looking presentable.

Even though the Fundacion provided for all their needs, they had to shine

their own shoes and wait on themselves in the dining room. The

City contained replicas of the offices in the Casa Rosada (where the President

worked but did not live). Students chose a president, ministers and diplomats

who were encouraged to offer suggestions and constructive criticism. Everyone

had a job to do, from welcoming newcomers and helping them to adapt to

the City or forming part of the nightly security patrol to holding an

elective office. Based on his personality, an adolescent might have his

own room or share a room with one or two other students. Students were

responsible for maintaining order in their own rooms and for looking presentable.

Even though the Fundacion provided for all their needs, they had to shine

their own shoes and wait on themselves in the dining room.

“They were to work towards the common good of the community but

not let themselves become the tool of someone else’s ambition,”

Evita told them, repeating an idea often expressed by Perón.

Much importance was given to Physical Education and sports. The City’s

“Clubs” took up two blocks and students had the right to belong

to one gym and two sports clubs: soccer, sword fighting, basketball, calisthenics,

running, swimming,diving, water polo, etc. A stadium, a barber shop, and

locker rooms completed the complex.

The

other two city blocks contained eight buildings which housed a dining

room, a “bar,” (which only served milk), a living The

other two city blocks contained eight buildings which housed a dining

room, a “bar,” (which only served milk), a living  room,

the bedrooms (for one, two, or a maximum of three students). room,

the bedrooms (for one, two, or a maximum of three students).

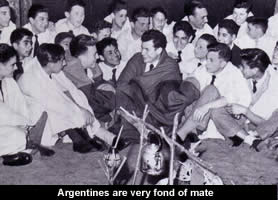

The students were a diverse group; they ranged from the sophisticated

natives of Buenos Aires, the porteños, to their country cousins

of the far North (Salta, Jujuy) and South (La Patagonia) and every effort

was made to integrate them using the common denominator of their Argentine

nationality. Extra curricular activites such as bonfires and drama school

helped. Argentines are very fond of mate, the herbal tea much loved by

the legendary gauchos, which they drink from a gourd with a silver straw,

la bombilla. At night the students would gather around a bonfire. Hot

water was added to the loose tea leaves and the gourd was passed from

person to person, the water and tea replenished as needed. Once a year,

during the “Ceremonia del Mate,” students would choose the

person they considered to have been the friendliest and most helpful during

the year.

Evita supervised all the details. For instance, she rejected some imported

glasses bearing the words “Sweet Dreams” in English because

she wanted to encourage pride in Argentina’s cultural heritage.

|

|

|

In 1952,

when her cortege was taken to Congress to lie in state, the students from

the Ciudad Estudiantil marched alongside the nurses of the Fundacion,

next to her coffin.

After the military coup d’etat of 1955, the students were evicted

and the buildings turned into a detention center to house the members

of government, arrested simply for being Peronistas. Later the Anti Infantile

Paralysis League took over the buildings.

Bibliography

Ferioli,

Néstor. La Fundación Eva Perón / 1. Buenos

Aires:Centro Editor de América Latina, 1990.

Fraser, Nicholas

& Marysa Navarro. Evita: The Real Life of Eva Perón.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996.

Ortiz, Alicia

Dujovne. Eva Perón. New York: St. Martin’s Press,

1996.

Fundación

Eva Perón. Eva Perón and Her Social Work. Buenos

Aires: Subsecretaria de Informaciones, 1950.

Fundación

Eva Perón. Cuidad Estudiantil. Buenos Aires: Subsecretaría

de Informaciones, 1954.

La Nación

Argentina: Justa, Libre, Soberana. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Peuser,

1950. |