The

Children’s City was not an amusement park although it brought joy

to thousands of children. It was a safe haven for children whose parents

were experiencing difficulties and needed long or short term help with

child care. As such, La Ciudad Infantil functioned in much the same way

as the Hogares Escuelas (see article on this website), having both day

students and residents. A motto from the Peronista Golden Age - those

early years of Perón’s first Presidency when The

Children’s City was not an amusement park although it brought joy

to thousands of children. It was a safe haven for children whose parents

were experiencing difficulties and needed long or short term help with

child care. As such, La Ciudad Infantil functioned in much the same way

as the Hogares Escuelas (see article on this website), having both day

students and residents. A motto from the Peronista Golden Age - those

early years of Perón’s first Presidency when  Evita

was alive and everything seemed possible- proclaimed that “the only

ones with privileges are the children.” Evita wanted the children

to be not only privileged but protected. Her Fundacion wove a safety net

stretching from childhood (the Hogares Escuelas for primary school children),

to adolescence (the Ciudad Estudiantil for secondary school children)

and beyond (the Ciudad Universitaria). Evita

was alive and everything seemed possible- proclaimed that “the only

ones with privileges are the children.” Evita wanted the children

to be not only privileged but protected. Her Fundacion wove a safety net

stretching from childhood (the Hogares Escuelas for primary school children),

to adolescence (the Ciudad Estudiantil for secondary school children)

and beyond (the Ciudad Universitaria).

The Ciudad Infantil, which sheltered children from two to seven years

of age, held an enchantment all its own. Social workers referred children

on a needs basis as stipulated by the Ciudad’s charter (very similar

to that of the Hogar Escuelas). At capacity, the Ciudad could take in

450 children; on an average, it held around 300, including residents and

day students.

The Children’s City was the apple of Evita’s eye. There she

could see the fruit of the sacrifices she was making in her own life.

Visitors from other countries commented that it was a model establishment,

well ahead of its time; its aim was to integrate marginalized  children

into society, prepare them for school and help them develop healthy relationships

by means of play. children

into society, prepare them for school and help them develop healthy relationships

by means of play.

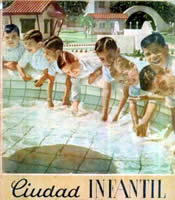

When people remember the Children’s City, they inevitably think

of its miniature buildings: chalets, the plaza with its splashing fountain,

the school, city hall,  the

Nordic style church with its vitraux, the gas station where pedal cars

were driven up to the pumps and the attendant was told to “fill

it up” , the police station where speeders were issued tickets,

the bank and shopping center with its assorted stores (pharmacy, greengrocer’s,

grocery store), and the azure stream which meandered through the city.

In the Children’s City, everyone had the chance to be mayor, banker,

pharmacist or teacher, but only for a day. Occupations were rotated, so

that each child could fulfill different roles in the community. the

Nordic style church with its vitraux, the gas station where pedal cars

were driven up to the pumps and the attendant was told to “fill

it up” , the police station where speeders were issued tickets,

the bank and shopping center with its assorted stores (pharmacy, greengrocer’s,

grocery store), and the azure stream which meandered through the city.

In the Children’s City, everyone had the chance to be mayor, banker,

pharmacist or teacher, but only for a day. Occupations were rotated, so

that each child could fulfill different roles in the community.

But the Ciudad Infantil was much more than a collection of miniature buildings.

The entire City occupied two blocks, bordered by four streets: Echeverria,

Húsares, Juramento and Ramsay in the Barrio Belgrano, a suburb

of Buenos Aires. One block was a large tree-shaded playground with slides,

teeter-totters, sandboxes, merry-go-rounds and an electric train. The

other block held the main building which housed the administrative offices,

a clinic, school rooms, a dining room with a capacity for 450  children,

four dormitories with a capacity for 110 children, a circus, a large hall

and a theater. Outside were solariums, a swimming pool and the miniature

city (an adult wishing to enter the buildings of the miniature city had

to stoop). children,

four dormitories with a capacity for 110 children, a circus, a large hall

and a theater. Outside were solariums, a swimming pool and the miniature

city (an adult wishing to enter the buildings of the miniature city had

to stoop).

Walls in the main building were decorated with drawings of the characters

familiar to children down through the ages: Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella,

the Three Little Pigs, circus animals. The dining room ceiling was scalloped

so it wouldn’t seem so high, and all the rooms were bright, spacious

and airy.

The children’s clothing came from the best shops in Buenos Aires

and was changed every four months. Children with shaven heads wearing

the drab uniforms of the Society of Beneficence had no place in the New

Argentina.

One detail illustrates the quality of care the children were given. The

dining room tables had tablecloths of three different colors, but the

yellow, pink and blue cloths were not part of a decorator’s color

scheme. The children were divided into three groups as recommended by

their dietitians. The caloric value given to the resident students was

based on their height and weight and contained the vitamins, minerals

and protein they needed to meet 100% of their daily requirements. The

day students, who might not be given a sufficient amount of nourishing

food at home, received 90% .

The children went to the Children’s Hotel in Chapadmalal for summer

vacations where many of them splashed in the Atlantic Ocean for the first

time in their lives.

If the home situation had not improved by the time the child was ready

for school, then that child was given priority of placement in a Hogar

Escuela.

Construction of the Ciudad Infantil went on day and night for five months

and twenty days. It was completed in record time and inaugurated on July

14, 1949, surely one of the happiest days of Evita’s life as wife

of the President. The old newsclips show her whirling around, almost dancing,

as she points out its features to those attending the inauguration. The

workers who had clocked the most hours presented her with “the keys

to the city” and told her that they knew that they were  working

for the good of their own children when they worked for the Fundacion.

The City was named “Cuidad Infantil Amanda Allen” after one

of the Fundacion nurses killed in a plane crash as she returned from helping

the victims of an earthquake in Ecuador. working

for the good of their own children when they worked for the Fundacion.

The City was named “Cuidad Infantil Amanda Allen” after one

of the Fundacion nurses killed in a plane crash as she returned from helping

the victims of an earthquake in Ecuador.

Her sister Erminda relates an anecdote which shows that the Ciudad Infantil

was never far from Evita’s thoughts. One day an elderly man went

to ask her to help him find work. “I really like the country,”

he stated. Evita felt that farm work would be too hard for him at his

age, so she told him, “I need you in the city. And I am going to

give you a job. I have been given three little donkeys for the children

of the Cuidad Infantil to ride on and I want you to take care of them

for me.” Erminda says that taking care of those donkeys made him

the happiest man alive.

Evita often visited the City unannounced, day and night. She would check

to see if there were enough supplies and ask for children by name if she

missed seeing them. Erminda relates how, when she knew she was dying,

she escaped from her doctors and went to visit the Ciudad Infantil. When

she returned to the Residence, she cried as she told her sister that the

level of care she had always insisted on was not being maintained.

After the military coup of 1955, the children in residence were evicted

and the establishment was turned into a nursery school for the children

of the upscale Belgrano neighborhood. Later the AntiInfantile Paralysis

League took over the administration buildings. In 1964, the author of

this article found out that the miniature city was scheduled for demolition

and appealed to the newspapers and magazines most sympathetic to the workers

whose contributions had made its construction possible. Newspapers wrote

articles, but the public had no power to stop the destruction and the

buildings were razed to make way for a parking lot.

What happened to the Ciudad Infantil is symbolic of the destruction of

Evita’s works. In the Argentina of the third millennium, children

are no longer privileged. Indeed, in a country capable of producing enough

food to feed the entire population of the United States, Argentine children

today are dying of starvation.

After the military took over Argentina in 1955, Evita’s works were

systematically destroyed or given other uses more in accordance with the

philosophy of the once again ruling classes (for instance, the military

turned the Children’s Hospital in Terma de Reyes into a luxury hotel

and casino for themselves and their families). As a reason for justifying

the dismantling of the Ciudad Infantil, the military investigative team

issued a report on December 5, 1955. We give them the last word: “The

attention given to the minors was varied, even sumptuous. One could even

say excessive and not at all in accordance with the sobriety which should

be part of the austere formation given to the children of a republic.

Fowl and fish formed a daily part of the children’s diet. And as

for clothing, their wardrobes were renewed every six months and the old

clothing destroyed.”

Bibliography

Ferioli,

Néstor. La Fundación Eva Perón / 2. Buenos

Aires:Centro Editor de América Latina, 1990.

Fraser, Nicholas

& Marysa Navarro. Evita: The Real Life of Eva Perón.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996.

Ortiz, Alicia

Dujovne. Eva Perón. New York: St. Martin’s Press,

1996.

Fundación

Eva Perón. Eva Perón and Her Social Work. Buenos

Aires: Subsecretaria de Informaciones, 1950.

La Nación

Argentina: Justa, Libre, Soberana. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Peuser,

1950.

|