Health

care was of vital importance to Perón and Evita. In 1950, A government

publication quoted Perón: Health

care was of vital importance to Perón and Evita. In 1950, A government

publication quoted Perón:

“The state must offer integral medical assistance to those who earn

least. Suppose I am a millionaire and I am taken ill . I would bring doctors

from all over the world, those specialists who charge $10-15,000 pesos

and I would have a good possibility of saving my life. The poor, on the

other hand, have no chance at all of doing that. But here in Buenos Aires,

in good hospitals, you have the possibility that an eminent physician

will take care of you. Just take a look at the interior of the country

where 50% of those who die do so without any medical attention.

“In the country of meat, in the country of bread, in the country

which has 300 days of sunlight a year, in the country where we have everything,

... the average life span is ten to twenty years less than Europe and

ten years less than in the U.S. Organizing public health can prolong our

lives an average of ten to twenty years.”

From Perón’s inauguration in 1946 until Evita’s death

in 1952, the government added 30,000 more hospital beds and the Fundación

added 15,000.

During his first Presidency, Perón was fortunate to have Dr. Ramón

Carrillo in the Ministry of Health. Dr. Carrillo was a visionary who revolutionized

health care in Argentina . His “Plan Analítico de Salud Pública”

(1947) outlined his ideas for humanizing medicine and making health care

accessible to all Argentines. These ideas were to be put into practice

when the Policlínico Presidente Peron was inaugurated in the working

class city of Avellaneda, Buenos Aires Province. The hospital consisted

of a complex of five wings, each six stories high (ground floor plus five)

with a capacity for 600 beds. The emergency room was on the ground floor,

as was an operating room, a library, a pharmacy, sterilization equipment

and laboratories for clinical analysis, bacteriology and research.

The first floor had an immense terrace for the relaxation of patients

and families, otorhinolaryngology; rheumatology; neurology; neuropsychiatry;

odontology; hematherapy, x-rays, ultrasound and physical therapy.

The wards were on the second floor and patients were separated by sex.

Each ward had three, four or six beds with screens to ensure privacy.

On one end of the hall was the chapel and on the other end the rooms where

the Fundacion nurses in training lived. There was also an amphitheater

which served as a conference room equipped with individual seats and movie

projectors where classes were held for doctors and nurses in training.

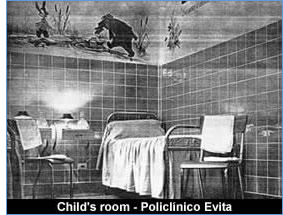

The

third floor was reserved for pre or post operative patients. A special

room for children, cheerful and spacious, was decorated with all the familiar

fairy tale figures. Social workers had their offices on this floor and

drew up a case study of each patient; their goal was to work with each

family unit and facilitate the practice of preventive medicine. The

third floor was reserved for pre or post operative patients. A special

room for children, cheerful and spacious, was decorated with all the familiar

fairy tale figures. Social workers had their offices on this floor and

drew up a case study of each patient; their goal was to work with each

family unit and facilitate the practice of preventive medicine.

The fourth floor was for gynecology, obstetrics, neonatology and pediatrics.

Nurses worked especially with first-time mothers.

The four operating theaters were on the fifth floor and two of them were

quite large so as to accommodate observers.

A small wing only one story high separated from the main complex housed

the morgue with autopsy rooms and a refrigeration room.

Another wing housed the outpatient clinics for pediatrics, gynecology,

obstetrics, dietetics, orthopedics, dermatology and general medicine.

The Policlínico Presidente Perón specialized in pneumology,

hematology and orthopedics, employing 1,500 people, 218 of which were

doctors and 491 of which were nurses; it also employed 32 kitchen workers,

as well as carpenters, plumbers, electricians, gardeners, and assorted

administrators. The Policlínico contracted outside employees such

as teachers (so the children would not fall behind in their schoolwork)

and home health care workers to assist in their homes those patients who

were either chronically ill or who could recover at home under medical

supervision.

Evita

wanted to see for herself that her high standards were being met and was

known to visit the Fundación’s works at night and unexpectedly. Evita

wanted to see for herself that her high standards were being met and was

known to visit the Fundación’s works at night and unexpectedly.

Néstor Ferioli interviewed Lala García Marín, a friend

of Evita’s who was in charge of a pharmacy open around the clock.

García Marín told him how Evita had appeared at the pharmacy

at one o’clock in the morning and asked García Marín

to accompany her to the Policlínico Presidente Perón. Distressed

at reports that the doctors in the emergency room were not attending the

patients according to hospital regulations, Evita decided to investigate.

She was dressed in slacks, and a vest, her hair loose around her shoulders,

tinted glasses hiding her eyes. An attendant told them they would have

to wait and Evita sat down obediently. They waited. No doctors appeared.

Evita sent Lala to ask if they would have to wait much longer for a doctor.

She was told to wait. The two women waited some more.

Evita told Lala, “Go ahead. Try again.”

Lala tried again. “Will the doctor be much longer?”

The attendant answered, “Here you have to wait. It’s not a

matter of arriving and being seen immediately.”

They waited a while longer. Suddenly Evita jumped up, took off her glasses

and told the attendant, “Get me the doctor in charge of the emergency

room - immediately!”

The attendant asked, “And who wants to see him?”

“Eva Perón!”

The

doctors came running in, fastening their smocks, sleep written all over

their faces. The

doctors came running in, fastening their smocks, sleep written all over

their faces.

Evita asked for the hospital’s Book of Rules, where all infractions

are noted, and began walking through the wards. She gently woke up and

interviewed every third or fourth patient. “How are you being treated?

Were you given the medicine you were supposed to have? Was the analysis

done?”

Of course, to the patients it all seemed like a dream. As soon as they

woke up enough to realize they really were talking to Evita, they began

to ask her for things for their children or grandchildren. Of course, to the patients it all seemed like a dream. As soon as they

woke up enough to realize they really were talking to Evita, they began

to ask her for things for their children or grandchildren.

One can imagine the changes that occured in the administration as word

spread that Evita ran a tight ship.

In 1951, the Policlínico Presidente Perón sent a Hospital

Train throughout Argentina. Equipped with operating and a delivery rooms,

it offered free medical attention, vaccinations, x-rays and medicine to

all who needed care.

The three policlíncos located in the Province of Buenos Aires,

Presidente Perón in Avellaneda , Eva Perón in Lanús

and Evita in San Martín, were considered triplets because their

layout and services were almost identical; they provided a wider range

of services than the thirteen other regional policlínicos. In addition

to the policlínicos, the Fundación constructed specialized

hospitals such as the Burn Institute in Buenos Aires, the Infectious Diseases

Hospital in Haedo, the Thorax  Surgery

Hospital in Ramos Mejía, and the 22 de Agosto Policlínico

in Ezeiza. Surgery

Hospital in Ramos Mejía, and the 22 de Agosto Policlínico

in Ezeiza.

High in the mountains of Jujuy nestled one of the crown jewels of the

Fundación’s hospital system, a combination hospital / hogar

escuela (for hogar escuela, see Education, Hogares Escuelas, this website)

designed to help children with kidney, rheumatic fever or nervous system

problems.  Located

in Terma de Reyes close to the capital city of Jujuy, the hospital had

a capacity for 144 sick children. A large swimming pool and smaller baths

were filled with thermal mineral waters from the Andes mountains. After

the 1955 military coup d’etat, the children were evicted and the

hospital turned into a casino and a hotel for military personnel and their

families. Located

in Terma de Reyes close to the capital city of Jujuy, the hospital had

a capacity for 144 sick children. A large swimming pool and smaller baths

were filled with thermal mineral waters from the Andes mountains. After

the 1955 military coup d’etat, the children were evicted and the

hospital turned into a casino and a hotel for military personnel and their

families.

In Buenos Aires, the Fundación almost completed what would have

been the largest children’s hospital in Latin America. Only finishing

touches were needed (adding plumbing fixtures, etc.) In September of 1955,

when the military took over Argentina, General Aramburu ordered a halt

to the construction. The building was totally abandoned and became a refuge

for derelicts and criminals (sometimes dead bodies were tossed over the

wall into the school yard next door).

In 1976,

at the beginning of the Dirty War (during which 30,000 Argentine men,

women and children were “disappeared” by their own government),

in an act heavy with symbolism, General Videla’s regime turned the

almost - completed children’s hospital into a concentration camp

for the victims of the military regime.

Bibliography

Ferioli,

Néstor. La Fundación Eva Perón / 2. Buenos

Aires:Centro Editor de América Latina, 1990.

Fraser, Nicholas

& Marysa Navarro. Evita: The Real Life of Eva Perón.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996.

Ortiz, Alicia

Dujovne. Eva Perón. New York: St. Martin’s Press,

1996.

Fundación

Eva Perón. Eva Perón and Her Social Work. Buenos

Aires: Subsecretaria de Informaciones, 1950.

Escuela

de Enfermeras. Buenos Aires: Subsecretaria de Informaciones, 1951.

La Nación

Argentina: Justa, Libre, Soberana. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Peuser,

1950.

|