|

|

|

The ladies of the Society of Beneficence ran School Homes, large austere buildings with drafty corridors and opaque windows so that the children inside could neither see out nor be seen. Clothed in identical drab uniforms, heads frequently shaven, called by the number sewed to their clothes instead of by their names, the children received more training than education. Emphasis was on school as work, workshop, sweatshop. Girls labored long hours sewing layettes for the wealthy society ladies who ran the asylums. Children often left the asylums only at Christmastime to stand on street corners and beg money for the maintenance of the Society of Beneficence.

Nor were the children the only ones exploited. A Congressional report in 1939 revealed that some employees of the Society of Beneficence worked 12 to 14 hours daily with a day off only every 10 or 15 days. Some had no days off and earned between 45-90 pesos at a time when the minimum wage was 120 pesos ( Diario de Sesiones de la Cámera de Diputados, 1939, p,444). In contrast, 95% of the funds at the disposition of the ladies of the Society went to pay the ladies’ salaries while only 5% went to maintain their works (Felipe Pigna, Página 12, 4/30/2007).

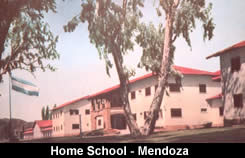

For Evita, the emphasis was on creating a home as a safe haven for children. We say that the eyes are the windows of the soul; the architecture of the twenty Home Schools (Hogares Escuela) established by the Fundación during the seven years before the 1955 military Coup d’Etat which overthrew Perón’s constitutionally elected government showed that the creation of a home was the nucleus or soul of these havens. Children went to public schools and maintained family ties whenever possible. Integration, not segregation, was the core of the Home Schools.

The architecture of the Home Schools reflected their openness to society. The hedge around the buildings was never more than a meter high. The buildings themselves were typical Fundación architecture: constructed in California mission style, wide and airy, full of light, with red tiled roofs, white walls and green lawns. The interior decoration was of the highest quality, with oak beds, mosaics and tiles which still stand after fifty years of abandonment and neglect. Cheerful tablecloths and an abundance of flowers, murals made to delight the eyes of a child, books and toys, all helped create a homelike atmosphere.

|

|

|

Home Schools sheltered about 16,000 children at a time when the population of  Argentina was about 16 million. They were built where the socioeconomic need was the greatest. Parents who wished their children to attend home schools had to write to Evita personally (they had to take the initiative) and while the Home School was being constructed, social workers and home visitors visited the families’ homes to corroborate each family’s situation and evaluate its needs. Argentina was about 16 million. They were built where the socioeconomic need was the greatest. Parents who wished their children to attend home schools had to write to Evita personally (they had to take the initiative) and while the Home School was being constructed, social workers and home visitors visited the families’ homes to corroborate each family’s situation and evaluate its needs.

The Fundación set a scale of priorities for admittance:

1. Material or moral abandonment

2. Illness of parents or guardians

3. Extreme poverty

4. Children whose parent/s had died

5. Irregular home life or separation of mother and father

6. Environmental causes (unhealthy living conditions or lack of basic necessities)

7. Economic instability caused by unemployment

8. Parents’ inability to care for children due to physical disability or illness

9. Advanced age of parents or guardians

10. Parent/s incarcerated

The children were admitted from ages four to ten (ages six to ten at Ezeiza). Children with physical or psychological problems were derived to the appropriate institutions and their treatment was paid for by the Fundación. Social workers worked with each family before and during the child’s stay at the Hogar Escuela. Evita did not want any child to be isolated from the world. All children were to have a nuclear family outside of the Hogar where they could spend weekends and holidays. If the child had no parents or could not return home for whatever reason, then a guardian was found for the child. The children were admitted from ages four to ten (ages six to ten at Ezeiza). Children with physical or psychological problems were derived to the appropriate institutions and their treatment was paid for by the Fundación. Social workers worked with each family before and during the child’s stay at the Hogar Escuela. Evita did not want any child to be isolated from the world. All children were to have a nuclear family outside of the Hogar where they could spend weekends and holidays. If the child had no parents or could not return home for whatever reason, then a guardian was found for the child.

Upon admittance, a complete medical workup was done for each child and after the first checkup, the children received two checkups a month with the emphasis on preventive medicine. Doctors, nurses, dentists, dietitians and hygienists were responsible for the health of Hogar staff and children.

The Hogar accommodated day children (who returned to their homes for dinner and to spend the night) and residents. All children received clothing (no uniforms-except the white smock which all Argentine children wore to public schools), shoes, books and school supplies, medications when necessary. Resident children were those who were poorest or who lived too far away to be transported on a daily basis. Day children were those whose parents were able to provide them with the basic necessities. Supplemental education, reinforcement, and tutoring were available as needed, but the children were transported by school bus to public schools.

When in the Hogar, the children were organized in groups of fifteen, with a preceptor, a kind of “nanny” in charge of each group. The children wore street clothing of their choice. Everything possible was done to avoid the “asylum mentality” so prevalent during the years of the Society of Beneficence. The children were not stigmatized or made to stand out in any way (no shaven heads, no use of a number instead of a name, no begging for funds). When in the Hogar, the children were organized in groups of fifteen, with a preceptor, a kind of “nanny” in charge of each group. The children wore street clothing of their choice. Everything possible was done to avoid the “asylum mentality” so prevalent during the years of the Society of Beneficence. The children were not stigmatized or made to stand out in any way (no shaven heads, no use of a number instead of a name, no begging for funds).

By 1954, the Department of Education had to make plans for first groups of Hogar children who had completed their primary education and were ready for high school. The Foundation only had one Home for( male) High School Students, la Ciudad Estudiantil, in Buenos Aires (these young people lived in the Ciudad Estudiantil but were bused to local high schools during the day). More Ciudades Estudiantiles were planned but had not yet been built. The Ministry of Education derived the students, according to abilities and vocations, to appropriate high schools. Since High School Homes for young women had not yet been completed, girls were allowed to continue in the Hogar as day students. The Hogar continued to give them clothes, food, medical attention, school supplies and books during their high school years; however, these privileges were lost if the girls received a fail in any school subject. Therefore, their grades were closely monitored and they were carefully supervised and tutored after school “just as any patient and intelligent mother would do for her children.”(Ferioli, La Fundación Eva Perón, vol. I, p. 77).

Supplementary after school classes such as dancing, folk dancing, cooking and sewing, music and art were held three times a week. Students were allowed to freely choose whatever interested them the most. In 1955 (before the September coup d’etat),the director of each Hogar was under strict orders “to encourage the young women to continue their post secondary studies at the Ciudad Universitaria de Córdoba (ibid, p. 78) which would have been inaugurated in 1956 “if Aramburu’s government had not paralyzed the construction” (ibid, p. 79). Supplementary after school classes such as dancing, folk dancing, cooking and sewing, music and art were held three times a week. Students were allowed to freely choose whatever interested them the most. In 1955 (before the September coup d’etat),the director of each Hogar was under strict orders “to encourage the young women to continue their post secondary studies at the Ciudad Universitaria de Córdoba (ibid, p. 78) which would have been inaugurated in 1956 “if Aramburu’s government had not paralyzed the construction” (ibid, p. 79).

Of course, after the military coup of 1955, the Society of Beneficence mentality became once again the order of the day. In a report dated December, 1955, the team who intervened in the Fundación documented their shock at finding that “the attention given to the minors was varied and almost sumptuous. We can even say that it was excessive and not at all in accordance with the norms of the sobriety of a Republic which should form its children in austerity. Of course, after the military coup of 1955, the Society of Beneficence mentality became once again the order of the day. In a report dated December, 1955, the team who intervened in the Fundación documented their shock at finding that “the attention given to the minors was varied and almost sumptuous. We can even say that it was excessive and not at all in accordance with the norms of the sobriety of a Republic which should form its children in austerity.

Poultry and fish were included in the varied daily menus. As for the [children’s] clothing, it was renewed every six months and the old clothing destroyed.” (See Ferioli, La Fundación Eva Perón, vol. I, pg. 87).

During his research into the 1945 San Juan earthquake, American historian Mark Healy found a legal file which illustrates how quickly Argentina returned to its past after the 1955 military Coup d’Etat. A woman lawyer, antiperonista, was instructed to intervene in the San Juan Hogar Escuela. She decided to turn it into an employment agency so that the girls, instead of going to college, could go to work as maids in the houses of people like her or her friends. The social workers employed by the school protested, as did the young girls who gathered in the patio to shout, “We want Perón to return!” (See Clarín, August 7, 2006, “Hogar Escuela de San Juan”).

By the time Perón did return in 1973, the Fundación Eva Perón had been plundered, dismantled, its works destroyed and the residents who had benefited most-children, students, seniors, working women, homeless families-scattered to the winds.

The military, like the Bourbons, had learned nothing and forgotten nothing. Evita, sadly and prophetically, once said, “I leave them the easiest task: that of changing the signs.” If only they had been content to change the signs on the buildings and leave the works intact! |

|

by

Dolane Larson by

Dolane Larson |

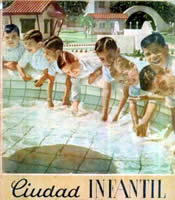

The

Children’s City was not an amusement park although it brought joy

to thousands of children. It was a safe haven for children whose parents

were experiencing difficulties and needed long or short term help with

child care. As such, La Ciudad Infantil functioned in much the same way

as the Hogares Escuelas (see article on this website), having both day

students and residents. A motto from the Peronista Golden Age - those

early years of Perón’s first Presidency when Evita

was alive and everything seemed possible- proclaimed that “the only

ones with privileges are the children.” Evita wanted the children

to be not only privileged but protected. Her Fundacion wove a safety net

stretching from childhood (the Hogares Escuelas for primary school children),

to adolescence (the Ciudad Estudiantil for secondary school children)

and beyond (the Ciudad Universitaria). The

Children’s City was not an amusement park although it brought joy

to thousands of children. It was a safe haven for children whose parents

were experiencing difficulties and needed long or short term help with

child care. As such, La Ciudad Infantil functioned in much the same way

as the Hogares Escuelas (see article on this website), having both day

students and residents. A motto from the Peronista Golden Age - those

early years of Perón’s first Presidency when Evita

was alive and everything seemed possible- proclaimed that “the only

ones with privileges are the children.” Evita wanted the children

to be not only privileged but protected. Her Fundacion wove a safety net

stretching from childhood (the Hogares Escuelas for primary school children),

to adolescence (the Ciudad Estudiantil for secondary school children)

and beyond (the Ciudad Universitaria).

The Ciudad Infantil, which sheltered children from two to seven years

of age, held an enchantment all its own. Social workers referred children

on a needs basis as stipulated by the Ciudad’s charter (very similar

to that of the Hogar Escuelas). At capacity, the Ciudad could take in

450 children; on an average, it held around 300, including residents and

day students.

The Children’s City was the apple of Evita’s eye. There she

could see the fruit of the  sacrifices she was making in her own life.

Visitors from other countries commented that it was a model establishment,

well ahead of its time; its aim was to integrate marginalized children

into society, prepare them for school and help them develop healthy relationships

by means of play. sacrifices she was making in her own life.

Visitors from other countries commented that it was a model establishment,

well ahead of its time; its aim was to integrate marginalized children

into society, prepare them for school and help them develop healthy relationships

by means of play.

When people remember the Children’s City, they inevitably think

of its miniature buildings: chalets, the plaza with its splashing fountain,

the school, city hall, the

Nordic style church with its vitraux, the gas station  where pedal cars

were driven up to the pumps and the attendant was told to “fill

it up” , the police station where speeders were issued tickets,

the bank and shopping center with its assorted stores (pharmacy, greengrocer’s,

grocery store), and the azure stream which meandered through the city.

In the Children’s City, everyone had the chance to be mayor, banker,

pharmacist or teacher, but only for a day. Occupations were rotated, so

that each child could fulfill different roles in the community. where pedal cars

were driven up to the pumps and the attendant was told to “fill

it up” , the police station where speeders were issued tickets,

the bank and shopping center with its assorted stores (pharmacy, greengrocer’s,

grocery store), and the azure stream which meandered through the city.

In the Children’s City, everyone had the chance to be mayor, banker,

pharmacist or teacher, but only for a day. Occupations were rotated, so

that each child could fulfill different roles in the community.

But the Ciudad Infantil was much more than a collection of miniature buildings.

The entire City occupied two blocks, bordered by four streets: Echeverria,

Húsares, Juramento and Ramsay in the Barrio Belgrano, a suburb

of Buenos Aires. One block was a large tree-shaded playground with slides,

teeter-totters, sandboxes, merry-go-rounds and an electric train. The

other block  held the main building which housed the administrative offices,

a clinic, school rooms, a dining room with a capacity for 450 children,

four dormitories with a capacity for 110 children, a circus, a large hall

and a theater. Outside were solariums, a swimming pool and the miniature

city (an adult wishing to enter the buildings of the miniature city had

to stoop). held the main building which housed the administrative offices,

a clinic, school rooms, a dining room with a capacity for 450 children,

four dormitories with a capacity for 110 children, a circus, a large hall

and a theater. Outside were solariums, a swimming pool and the miniature

city (an adult wishing to enter the buildings of the miniature city had

to stoop).

Walls in the main building were decorated with drawings of the characters

familiar to children down through the ages: Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella,

the Three Little Pigs, circus animals. The dining room ceiling was scalloped

so it wouldn’t seem so high, and all the rooms were bright, spacious

and airy.

The children’s clothing came from the best shops in Buenos Aires

and was changed every four months. Children with shaven heads wearing

the drab uniforms of the Society of Beneficence had no place in the New

Argentina.

One detail illustrates the quality of care the children were given. The

dining room tables had tablecloths of three different colors, but the

yellow, pink and blue cloths were not part of a decorator’s color

scheme. The children were divided into three groups as recommended by

their dietitians. The caloric value given to the resident students was

based on their height and weight and contained the vitamins, minerals

and protein they needed to meet 100% of their daily requirements. The

day students, who might not be given a sufficient amount of nourishing

food at home, received 90% . One detail illustrates the quality of care the children were given. The

dining room tables had tablecloths of three different colors, but the

yellow, pink and blue cloths were not part of a decorator’s color

scheme. The children were divided into three groups as recommended by

their dietitians. The caloric value given to the resident students was

based on their height and weight and contained the vitamins, minerals

and protein they needed to meet 100% of their daily requirements. The

day students, who might not be given a sufficient amount of nourishing

food at home, received 90% .

The children went to the Children’s Hotel in Chapadmalal for summer

vacations where many of them splashed in the Atlantic Ocean for the first

time in their lives.

If the home situation had not improved by the time the child was ready

for school, then that child was given priority of placement in a Hogar

Escuela.

Construction of the Ciudad Infantil went on day and night for five months

and twenty days. It was completed in record time and inaugurated on July

14, 1949, surely one of the happiest days of Evita’s life as wife

of the President. The old newsclips show her whirling around, almost dancing,

as she points out its features to those attending the inauguration. The

workers who had clocked the most hours presented her with “the keys

to the city” and told her that they knew that they were working

for the good of their own children when they worked for the Fundacion.

The City was named “Cuidad Infantil Amanda Allen” after one

of the Fundacion nurses killed in a plane crash as she returned from helping

the victims of an earthquake in Ecuador.

Her sister Erminda relates an anecdote which shows that the Ciudad Infantil

was never far from Evita’s thoughts. One day an elderly man went

to ask her to help him find work. “I really like the country,”

he stated. Evita felt that farm work would be too hard for him at his

age, so she told him, “I need you in the city. And I am going to

give you a job. I have been given three little donkeys for the children

of the Cuidad Infantil to ride on and I want you to take care of them

for me.” Erminda says that taking care of those donkeys made him

the happiest man alive.

Evita often visited the City unannounced, day and night. She would check

to see if there were enough supplies and ask for children by name if she

missed seeing them.  Erminda relates how, when she knew she was dying,

she escaped from her doctors and went to visit the Ciudad Infantil. When

she returned to the Residence, she cried as she told her sister that the

level of care she had always insisted on was not being maintained. Erminda relates how, when she knew she was dying,

she escaped from her doctors and went to visit the Ciudad Infantil. When

she returned to the Residence, she cried as she told her sister that the

level of care she had always insisted on was not being maintained.

After the military coup of 1955, the children in residence were evicted

and the establishment was turned into a nursery school for the children

of the upscale Belgrano neighborhood. Later the AntiInfantile Paralysis

League took over the administration buildings. In 1964, the author of

this article found out that the miniature city was scheduled for demolition

and appealed to the newspapers and magazines most sympathetic to the workers

whose contributions had made its construction possible. Newspapers wrote

articles, but the public had no power to stop the destruction and the

buildings were razed to make way for a parking lot.

What happened to the Ciudad Infantil is symbolic of the destruction of

Evita’s works. In the Argentina of the third millennium, children

are no longer privileged. Indeed, in a country capable of producing enough

food to feed the entire population of the United States, Argentine children

today are dying of starvation.

After the military took over Argentina in 1955, Evita’s works were

systematically destroyed or given other uses more in accordance with the

philosophy of the once again ruling classes (for instance, the military

turned the Children’s Hospital in Terma de Reyes into a luxury hotel

and casino for themselves and their families). As a reason for justifying

the dismantling of the Ciudad Infantil, the military investigative team

issued a report on December 5, 1955. We give them the last word: “The

attention given to the minors was varied, even sumptuous. One could even

say excessive and not at all in accordance with the sobriety which should

be part of the austere formation given to the children of a republic.

Fowl and fish formed a daily part of the children’s diet. And as

for clothing, their wardrobes were renewed every six months and the old

clothing destroyed.”

Bibliography

Ferioli,

Néstor. La Fundación Eva Perón / 2. Buenos

Aires:Centro Editor de América Latina, 1990.

Fraser, Nicholas

& Marysa Navarro. Evita: The Real Life of Eva Perón.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996.

Ortiz, Alicia

Dujovne. Eva Perón. New York: St. Martin’s Press,

1996.

Fundación

Eva Perón. Eva Perón and Her Social Work. Buenos

Aires: Subsecretaria de Informaciones, 1950.

La Nación

Argentina: Justa, Libre, Soberana. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Peuser,

1950.

|

| |

by

Dolane Larson by

Dolane Larson |

La Ciudad Estudiantil, the Students’ City, was located next to the Children’s City in the Buenos Aires suburb of Belgrano. It took up four city blocks: Echeverría, Ramsay, Dragones, and Blanco Encalada. La Ciudad Estudiantil, the Students’ City, was located next to the Children’s City in the Buenos Aires suburb of Belgrano. It took up four city blocks: Echeverría, Ramsay, Dragones, and Blanco Encalada.

The Students’ City was organized in the same way as the Hogares Escuelas (“Home Schools”; see article on this site). Transported each day in Fundación buses, students studied in regular high schools, in specialized business and industrial schools and in the Engineering, Law, and Medicine Colleges (Facultades). When they returned home at the end of the school day, professors were waiting to tutor them. Classes were also taught at the Ciudad Estudiantil and emphasis was placed on the latest technology so that the students would be successful in the modern world. The instruction they received was so advanced that after the military closed the school, students received scholarships to study in other countries anxious to take advantage of their knowledge and talents.

Both the Ciudad Infantil, with its Montessori classes which encouraged individual inactive, and the Ciudad Estudiantil, with its emphasis on “high tech”, were ahead of their time. The purpose of the Ciudad Estudiantil was not only to function as a Hogar Escuela for adolescents in need but also to prepare future leaders from among the working classes by involving them in the decision-making process of governing the Ciudad Estudiantil. Both the Ciudad Infantil, with its Montessori classes which encouraged individual inactive, and the Ciudad Estudiantil, with its emphasis on “high tech”, were ahead of their time. The purpose of the Ciudad Estudiantil was not only to function as a Hogar Escuela for adolescents in need but also to prepare future leaders from among the working classes by involving them in the decision-making process of governing the Ciudad Estudiantil.

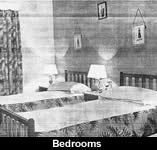

All students were male. Since the Fundacion did not yet have a Ciudad Estudiantil for females, adolescent girls continued to be under the protection of the Hogares Escuelas; they received food, clothes, medical attention, tuition to secondary schools, books, supplies, everything they needed to complete their secondary schooling and continue at the university level (the only condition was that they had to pass all their classes, but tutoring was  always available). The City contained replicas of the rooms in the Casa Rosada (where the President works but does not live). Students chose a president, ministers and diplomats who were encouraged to offer suggestions and constructive criticism, forming a co-government of instructors and students. Everyone had a job to do, from welcoming newcomers and helping them to adapt to the City , forming part of the nightly security patrol or holding an elective office. Based on his personality, an adolescent might have his own room or share a room with one or two other students. Students were responsible for keeping their rooms neat and for looking presentable themselves, obtaining points according to their achievements. To continue in the Ciudad Estudiantil, students had to maintain a certain number of points based on their studies and their conduct, both in and out of the Ciudad. Even though the Fundacion provided for all their needs, they had to shine their own shoes and wait on themselves in the dining room. always available). The City contained replicas of the rooms in the Casa Rosada (where the President works but does not live). Students chose a president, ministers and diplomats who were encouraged to offer suggestions and constructive criticism, forming a co-government of instructors and students. Everyone had a job to do, from welcoming newcomers and helping them to adapt to the City , forming part of the nightly security patrol or holding an elective office. Based on his personality, an adolescent might have his own room or share a room with one or two other students. Students were responsible for keeping their rooms neat and for looking presentable themselves, obtaining points according to their achievements. To continue in the Ciudad Estudiantil, students had to maintain a certain number of points based on their studies and their conduct, both in and out of the Ciudad. Even though the Fundacion provided for all their needs, they had to shine their own shoes and wait on themselves in the dining room.

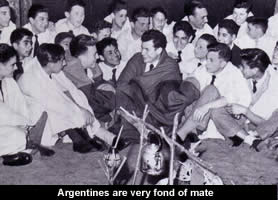

“They were to work towards the common good of the community but not let themselves become the tool of someone else’s ambition,” Evita told them, repeating an idea often expressed by Perón. Much importance was given to Physical Education and sports. The City’s “Clubs” took up two blocks and students had the right to belong to one gym and two sports clubs: soccer, sword fighting, basketball, calisthenics, running, swimming,diving, water polo, etc. A doctor and dentist consulting room, a stadium, a barber shop, and locker rooms completed the complex. The other two city blocks contained eight buildings which housed a dining room, a “bar,” (which only served milk), a living room, the bedrooms (for one, two, or a maximum of three students). The students were a diverse group; they ranged from the porteños, sophisticated natives of Buenos Aires, to their country cousins of the far North (Salta, Jujuy) and South (La Patagonia) and every effort was made to integrate them using the common denominator of their Argentine nationality. Extra curricular activities such as bonfires and drama school helped. Argentines are very fond of mate, the herbal tea much loved by the legendary gauchos, which they drink with a silver straw, la bombilla, from a hollowed-out gourd . At night the students would gather around a bonfire. Hot water was added to the loose tea leaves and the gourd was passed from person to person, the water and tea replenished as needed. Once a year, during the “Ceremonia del Mate,” residents would choose the student they considered to have been the friendliest and most helpful. Evita supervised all the details. For instance, she rejected some imported glasses bearing the words “Sweet Dreams” in English because she wanted to encourage pride in Argentina’s cultural heritage. “They were to work towards the common good of the community but not let themselves become the tool of someone else’s ambition,” Evita told them, repeating an idea often expressed by Perón. Much importance was given to Physical Education and sports. The City’s “Clubs” took up two blocks and students had the right to belong to one gym and two sports clubs: soccer, sword fighting, basketball, calisthenics, running, swimming,diving, water polo, etc. A doctor and dentist consulting room, a stadium, a barber shop, and locker rooms completed the complex. The other two city blocks contained eight buildings which housed a dining room, a “bar,” (which only served milk), a living room, the bedrooms (for one, two, or a maximum of three students). The students were a diverse group; they ranged from the porteños, sophisticated natives of Buenos Aires, to their country cousins of the far North (Salta, Jujuy) and South (La Patagonia) and every effort was made to integrate them using the common denominator of their Argentine nationality. Extra curricular activities such as bonfires and drama school helped. Argentines are very fond of mate, the herbal tea much loved by the legendary gauchos, which they drink with a silver straw, la bombilla, from a hollowed-out gourd . At night the students would gather around a bonfire. Hot water was added to the loose tea leaves and the gourd was passed from person to person, the water and tea replenished as needed. Once a year, during the “Ceremonia del Mate,” residents would choose the student they considered to have been the friendliest and most helpful. Evita supervised all the details. For instance, she rejected some imported glasses bearing the words “Sweet Dreams” in English because she wanted to encourage pride in Argentina’s cultural heritage.

In 1952, when her cortege was taken to Congress to lie in state, the students from the Ciudad Estudiantil marched alongside the nurses of the Fundacion, next to her coffin. After the military coup d’etat of 1955, the students were evicted and the buildings turned into a detention center to house the members of government, arrested simply for being Peronistas. Later the Anti Infantile Paralysis League took over the buildings.

Bibliography

Ferioli,

Néstor. La Fundación Eva Perón / 1. Buenos

Aires:Centro Editor de América Latina, 1990.

Fraser, Nicholas

& Marysa Navarro. Evita: The Real Life of Eva Perón.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996.

Ortiz, Alicia

Dujovne. Eva Perón. New York: St. Martin’s Press,

1996.

Fundación

Eva Perón. Eva Perón and Her Social Work. Buenos

Aires: Subsecretaria de Informaciones, 1950.

Fundación

Eva Perón. Cuidad Estudiantil. Buenos Aires: Subsecretaría

de Informaciones, 1954.

La Nación

Argentina: Justa, Libre, Soberana. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Peuser,

1950. |

| |

by

Dolane Larson by

Dolane Larson |

“In 1953, supervised by the Department of Architecture, under the auspices of the Ministry of Public Works, the Fundacion began constructing two university cities in the provinces of Córdoba and Mendoza. These cities were to have a large central pavilion for classrooms and cafeterias and other smaller residence buildings for professors and students. The University City of Córdoba would have been inaugurated by December of 1956, but General Aramburu1 , the head of the military government at the time, ordered construction stopped. “In 1953, supervised by the Department of Architecture, under the auspices of the Ministry of Public Works, the Fundacion began constructing two university cities in the provinces of Córdoba and Mendoza. These cities were to have a large central pavilion for classrooms and cafeterias and other smaller residence buildings for professors and students. The University City of Córdoba would have been inaugurated by December of 1956, but General Aramburu1 , the head of the military government at the time, ordered construction stopped.

The Fundacion was able to complete a cafeteria for university students in the city of La Plata, in the Province of Buenos Aires.”

Bibliography

Ferioli, Néstor. La Fundación Eva Perón / 1. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina, 1990, pgs. 78-79.

La Nación Argentina: Justa, Libre, Soberana. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Peuser, 1950.

|

|